As Generous as Gentle Rain

On negative space, vanishing lines, and room to breathe in calligraphy and poetry

I’ve been busy the past week with a multitude of tasks in my new house, so this our post will be lighter than usual. Rest assured, there’s plenty of new translation and book reviews in progress. Stay tuned.

Last week we met a new friend 虛 xu, a word I translated as “not full.” (Or, when applied to mental states, “vacant.”) Along with “full” 實 shi, xu represents the “yin” or “negative” side of a complete aesthetic in Chinese philosophy.1 Balance between fullness and vacancy, and especially their dynamic interplay of wax and wane, gives a piece of art a living, “breathing” feel.

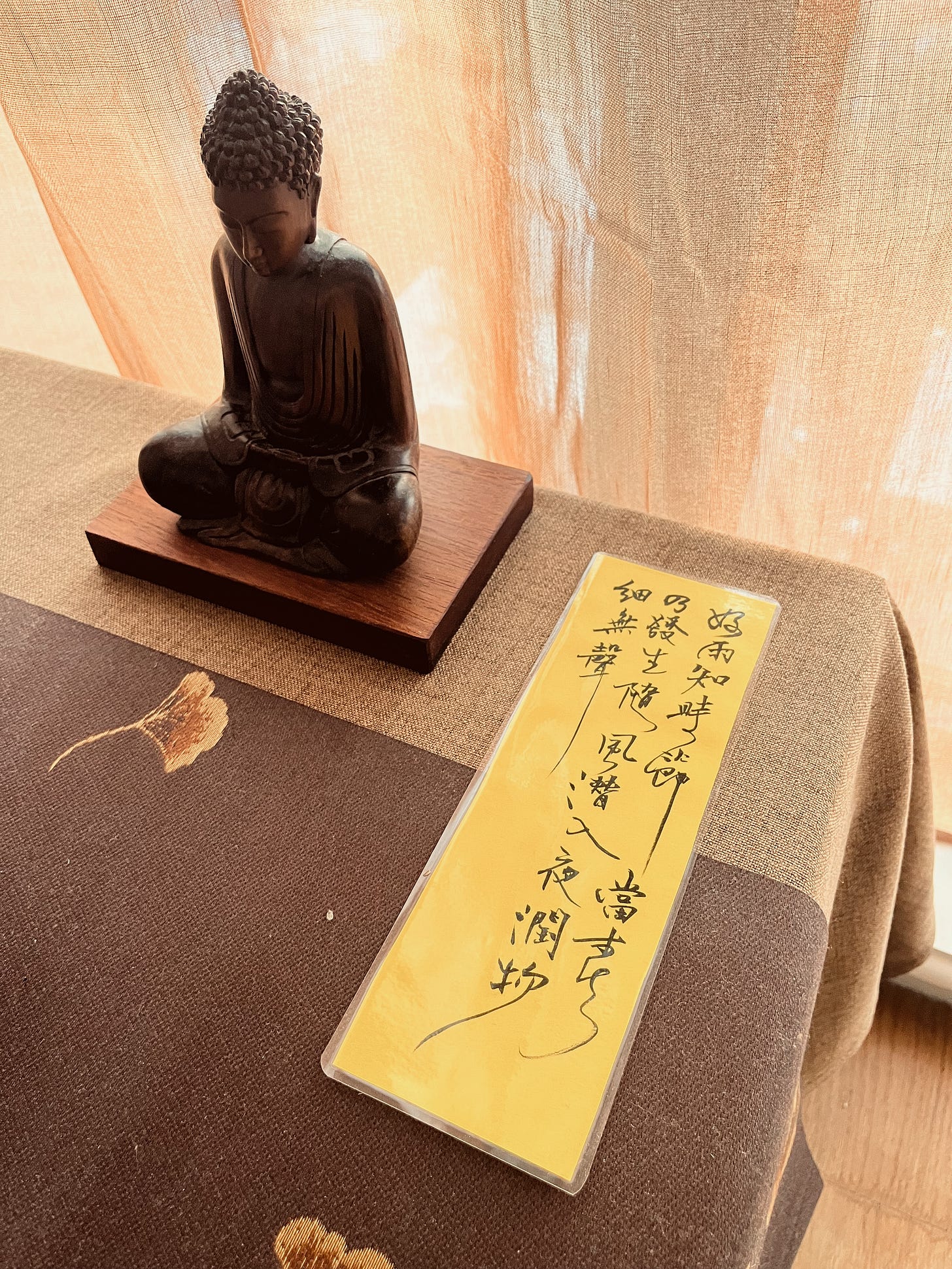

To get a sense of what xu means, let’s look at a small, modern work by an accomplished calligrapher.

Chinese characters are of course a technology for communication, but calligraphic style was historically also a rich, diverse sphere of art and personal cultivation. Luckily, you don’t need to read characters to appreciate them as art.

When I look at a piece of calligraphy, I experience the artist’s fluid state of mind and body, which is captured in the flow of the brush. That flow is precisely the meaning of the term 氣 qi.2

For artists, the qi of a piece is intimately connected to the breath of its maker. Chinese calligraphy happens in one continuous set of movements, and especially in a semi-cursive style of this piece, the brush is always moving.

Because calligraphy brushes are soft and very flexible, each stroke of ink captures fine gradations of force and momentum. In each dynamic line, you can see how the artist applies force (thick or thin) and control (whether a line is solid along the edges or faint).

If this sounds like xu and shi…you’re spot on. Most Chinese art focuses on balance between full and not full, but not necessarily through symmetry. Instead, there are generally less elements that are “heavier” shi and more that are “lighter” xu.

Often, you’ll see a lot of negative space and a lot less “stuff.”3 This is because more xu elements are needed to balance the fullness of shi elements.

Let’s look closer at this piece.

Even if you don’t read any Chinese, you might notice the long, flowing lines after certain characters. These are accents, added by the artist, that don’t change the meaning of the poem at all. They taper off into the next word…or into vacuity. In other words, there’s a lot of xu here.

Those tapering lines don’t impact a person’s ability to read this poem, but they are absolutely not the standard way to write. Their lengthened flow represent deliberate but spontaneous artistic choices that happen within milliseconds. Experienced calligraphers are concentrated but relaxed, creating their art in one fast and intuitive swoop of the brush.4

In semi-cursive script, it’s even possible to feel the entire flow of the artist’s qi throughout the piece, because each movement of the brush connects to the next movement.

Look at the character in the top right. When written from top to bottom, do you see how the line begins strong and solid (shi) and then weakens as it trails off (xu)?

The line’s direction and diminishing strength is not accidental: the brush is leaving the page. But the artist already knows what comes next. Though the brush no longer touches the page, its movement transitions seamlessly into the next stroke.

Look closely at the horizontal line directly below the character I just mentioned. It begins from the left with a tiny little hook. The precise size and direction of that hook is connected to the previous movement: the new position of the brush flows from its last position.

Every momentary dab of ink is connected. Connected, and unique. Unique to the force and direction of brushstrokes in the previous moment and the next moment.

If you know the rules of how to write each character, you can actually follow this movement throughout an entire piece, stroke by stroke, tracing the artist’s energy and breath (qi) long after they have put down their brush.

Of course, just as dance is also movement, calligraphy is also writing. And writing carries meaning.

In this case, this is the first stanza of an extremely famous Tang Dynasty poem by Du Fu, extolling the virtues of spring rain. I’ve rendered the poem into English twice.

A good rain knows its proper time

When spring bursts forth imminently

How fine! It sinks through night on breeze

Refreshing all things, silently

This first version tries to express the literal meaning of the poem. I’ve rearranged some words due to metrical considerations, but overall, these are roughly the same words you’d find in Chinese.

A fine rain knows the proper time—

When spring bursts forth imminently—

To soak the night in breeze. All things

Refreshing; gently, silently.

This version is freer in structure and word choice, and aims to capture the original imagery rather than structure or words.

As a result, there is also more “empty space,” room for the poem and reader to breathe and interpret. I think this version is a better fit for the xu accents in the calligraphy.

One note on wording. “Refresh” here translates the character 潤 rùn. Run literally means “to moisten”, but it carries strong overtones of nourishment and nurturing. Physically, for sure, but also morally and ethically.

This stanza’s last line, 潤物細無聲, is a very well-known phrase even in Modern China. In describing the spring rain, it expresses a moral ideal of selfless, non-discriminatory generosity.

Which version do you prefer? The first, more literal, more “full” (shi) translation, or the second, freer, “less full” (xu) translation?

The tapered lines in this piece of calligraphy and the “space” that they leave for the viewer were not contrived or planned. They emerged naturally from the artist’s understanding of the written words, personal aesthetic, and mental condition. So too did the original poem. (And, to some degree, my translation.)

Next week, we’ll get another passage from the Dao De Jing and continue reading another chapter of The Extinction of Experience.

陰 Yīn and 陽 yáng are often associated with feminine and masculine energies, but like most applications of these terms, they are extended rather than core meanings. The feminine/masculine association comes from the fundamental (and fairly misogynist) binary of “full [of energy]” and “not full [of energy].” Please don’t read gender into every (or even most) usages of shi and xu.

Yup, this is the qi you probably know from, I dunno, kung fu or acupuncture. Qi literally means “air” and often refers to breath, but it’s not wrong to think of it as (we often do in the West as) “energy” or “life-force”. As a concept with thousands of years of deep history and resonance, it means different things in different contexts, but always carries the core idea of “energy that animates.”

In Chinese this is called 留白 liú bái, literally “leaving white [space]”. This term comes from painting but can be used metaphorically in many, many contexts to describe negative space in an image, a text, music, or even thoughts.

Chinese calligraphy is such a rich art because black lines on a white page encode a surprising amount of information! A discerning eye can tell how concentrated and relaxed the artist is from the quality of lines they produce. I’m not an expert by any means, but I do know enough to look at a piece and know something about the artist’s mental and physical state. This is why I particularly enjoy looking at calligraphy: you can feel the breath, flow, and life of a human being by looking at dead ink on paper.

What an eloquent tribute to calligraphy and poetry.

I prefer the second translation, as I feel "to soak the night in breeze' follows smoothly from the previous line. Stephen Owen has the first three lines as

'A good rain knows its appointed time,

right in spring it brings things to life.

It enters the night unseen with the wind'

which of course is a great translation - it's Owen - but I love the way you have "When spring bursts forth imminently" - this line rings with rhythm and the onomatopoeic

sounds of 'imminently', almost sounding like raindrops gently dripping.

(And i like your translation much more than Owen's)

The way you describe the process of calligraphy and the 气 in the writing is fascinating. Could you share who wrote these elegant words?